1. Introduction

Agroforestry is agricultural approach in which different crops and perennial wood trees are grown together on the same plot of land unit

| [24] | Owonubi, J. and Otegbeye, G. (2002), Disappearing Forest: a review of the Challenges for Conservation of genetic resources and environmental management. J. Forestry. Res. Manage. 1 (1/2): 1-11. |

[24]

. Agroforestry practices cover an entire spectrum of land use systems in which woody perennials are deliberately combined with crops and/or animals in some spatial or temporal arrangement

| [30] | Sobola, O., Amadi, C., Jamala, Y. (2015). The Role of Agroforestry in Environmental Sustainability. IOSR Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science (IOSR-JAVS), Volume 8, 5, I, PP 20-25. |

[30]

.

Nowadays, food security has long been an issue that has attracted global attention under a situation of urbanization and climate change by which the total area of active farmland continues to decrease

| [6] | Devereux, S, and Maxwell S. (2001). Food Security in Sub-Saharan Africa. ITDG Publishing, London. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2008. Climate change for fisheries and aquaculture: Technical background document from the expert consultation held on 7-9 April 2008, Rome. |

| [31] | Tannis Th. and Henry, N. (2012). Reducing subsistence farmers’ vulnerability to climate change: evaluating the potentialcontributions of agroforestry in western Kenya. Agriculture & Food Security, https://doi.org/10.1186/2048-7010-1-15 |

[6, 31]

. It seems like insufficient attention has been paid to processes that increase crop yield, leading to an increase in the multiple cropping indexes. Within the recent widening of environmental degradation and climate change, increased food production is difficult to be realized from farmland expansion in many regions

| [33] | Von B (2007) Rising world food prices: impact on the poor. The International Journal for Rural Development (Rural 21) 42: 19–21. |

[33]

.

However, agroforestry is an effective method for improving crop productivity as it is an efficient use of natural resources and human resources

| [21] | Oke, O. S. et al. (2023). Involvement of selected arable crop farmers in agro-forestry practices in Ekiti state, Nigeria. UNIZIK Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 2(1). |

[21]

. The practice of mixed cropping also helps to alleviate competition for land use quite important for adapting to climate change

| [28] | Scherr, J. (2002). Introduction. Trees on the Farm: Assessing the Adoption Potential of Agroforestry Practices in Africa. Edited by: Franzel S, Scherr J. 2002, New York, Cabi Publishing. |

| [29] | Schroth, G. and Ruf F. (2014). Farmer strategies for tree crop diversification in the humid tropics. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, Springer Verlag/EDP Sciences/INRA, 34 (1), pp. 139-154. |

[28, 29]

. According to Akinnagbe and Irohibe

| [2] | Akinnagbe O. M. And Irohibe I. J. (2014). Agricultural Adaptation Strategies to Climate Change Impacts in Africa: A Review, Bangladesh J. Agril. Res. 39(3): 407-418. |

[2]

, climate change is feasible to be the most severe in developing countries, ultra-poor, located in tropical and subtropical regions, or in semi-desert zones with disadvantaged economies which are predominantly vulnerable to uneven weather patterns and rising temperatures.

As Sobola, Amadi & Jamala,

| [30] | Sobola, O., Amadi, C., Jamala, Y. (2015). The Role of Agroforestry in Environmental Sustainability. IOSR Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science (IOSR-JAVS), Volume 8, 5, I, PP 20-25. |

[30]

pointed out agro-forestry practices are being increasingly advocated as possible remedies as it is a land use system that has the potential to improve agricultural land use while providing lasting benefits and alleviating adverse environmental effects at local and global levels. They also identified as agroforestry has been known to have the ability of reducing carbon emissions from deforestation and forest degradation land. Moreover, as Nyong, Adesina and Elasha

| [20] | Nyong, A., Adesina F. and O. Elasha (2007). The value of indigenous knowledge in climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies in the African Sahel. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Change. 12, Pp. 787-797. |

[20]

it promotes sustainable forest management as well as the conservation and sustainability of the environment. It is therefore vital to employ, agroforestry to encourage increasing productivity as well as environmental stability.

The increasing impacts of climate change on agriculture can advance the pursuit to practice agroforestry. Not only that it also needs to diversification of crop farming in agroforestry practices for sustainability and diversifying farm income sources

| [23] | Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2009). Climate change in West Africa: Sahelian adaptation strategies. SWAC briefing note, no. 3, January, Pp. 4-6. |

[23]

. According to Schroth and Ruf

| [29] | Schroth, G. and Ruf F. (2014). Farmer strategies for tree crop diversification in the humid tropics. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, Springer Verlag/EDP Sciences/INRA, 34 (1), pp. 139-154. |

[29]

"who do not put all eggs into one basket tend to be less vulnerable than producers who are largely dependent on a single crop" when elucidates the essentiality of diversification in humid tropic crop farming. Furthermore, he identified that where individual crops only produce one or two harvests per year, crop diversification can improve the income distribution over the year.

Ethiopia has features of undulating topography and is highly dependent on rain-fed agriculture. In addition, there are problems of under-development of water resources, high population growth rate, low economic development level, drought reoccurrence, and weak institutions in combination with low adaptive capacity

| [9] | Gangadhara, H., & Moges, D. M. (2021). Climate change and its implications for rainfed agriculture in Ethiopia. Journal of Water and Climate Change, 12(4), 1229–1244. https://doi.org/10.2166/wcc.2020.058 |

[9]

. These resulted in Ethiopia as one of the most vulnerable East African countries to the adverse effects of climate change

| [11] | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2007). Climate Change 2007: Climate change impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability - Summary for policymakers. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC. |

[11]

. Even temperature has been increasing by about 0.37°C every ten years

| [18] | National Adaptation Program Action (NAPA), (2007). Report on Preparation of National Adaptation Programme of Action for Ethiopia" supported by the GEF through the UNDP. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. |

[18]

.

Farmers allowing crop diversification under crops like coffee will bring gradually to adapt a changing to environment through transition process from one dominant crop to another. This plays greater role in increasing farmers flexibility and adaptive capacity

| [7] | Ewunetu T and Zebene S. (2018) Tree Species Diversity, Preference and Management in Smallholder Coffee Farms of Western Wellega, Ethiopia. |

| [29] | Schroth, G. and Ruf F. (2014). Farmer strategies for tree crop diversification in the humid tropics. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, Springer Verlag/EDP Sciences/INRA, 34 (1), pp. 139-154. |

[7, 29]

.

According to different studies, in most African countries crop farming is mainly subsistence and rain-fed

| [5] | Collier P, Conway G. and Venables T. (2008). Climate change and Africa. Oxford Review of economic policy 24 (2), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grn019 |

| [16] | Lema, M. A. and Majule, A. (2009). Impacts of climate change, variability and adaptation strategies on agriculture in semi-arid areas of Tanzania: The case of Manyoni District in Singida Region, Tanzania. African Journal of Environmental Science and (1)Technology. 3 (8), Pp. 206-218. |

[5, 16]

. Such kinds of farming systems are highly affected by climate change and untimely rain during harvest of production

| [6] | Devereux, S, and Maxwell S. (2001). Food Security in Sub-Saharan Africa. ITDG Publishing, London. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2008. Climate change for fisheries and aquaculture: Technical background document from the expert consultation held on 7-9 April 2008, Rome. |

[6]

. And it is resulting in a decline of food production and it makes Africa particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Their vulnerability is further exacerbated by as the area already found in hot as it is tropical zone

| [2] | Akinnagbe O. M. And Irohibe I. J. (2014). Agricultural Adaptation Strategies to Climate Change Impacts in Africa: A Review, Bangladesh J. Agril. Res. 39(3): 407-418. |

| [5] | Collier P, Conway G. and Venables T. (2008). Climate change and Africa. Oxford Review of economic policy 24 (2), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grn019 |

| [28] | Scherr, J. (2002). Introduction. Trees on the Farm: Assessing the Adoption Potential of Agroforestry Practices in Africa. Edited by: Franzel S, Scherr J. 2002, New York, Cabi Publishing. |

[2, 5, 28]

.

According to Rosenstock et al

| [27] | Rosenstock et al (2018). Making Trees count in Africa: Improved MRV is needed to Meeting Africa’s Agroforestry Ambition. CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), Wageningen, Netherlands. http://doi.org/0.1038/srep29987 |

[27]

and Scherr

| [28] | Scherr, J. (2002). Introduction. Trees on the Farm: Assessing the Adoption Potential of Agroforestry Practices in Africa. Edited by: Franzel S, Scherr J. 2002, New York, Cabi Publishing. |

[28]

despite there is the intention to expand agroforestry practices throughout the world, significant gaps exist between countries on desires and their capabilities to practice multiple crops of agroforestry. There is also a gap in the study of the contribution of the diversification of crops in agroforestry to tackle the influence of climate variability challenges and diversify farm income. There is a need to prepare strategies and indicators at all levels to plan farming of diversified agroforestry systems that benefit society to adapt to climate variability.

While mixed crop and agroforestry systems are globally of considerable importance, their likely roles in reducing climate change are not that well understood in Ethiopia

| [18] | National Adaptation Program Action (NAPA), (2007). Report on Preparation of National Adaptation Programme of Action for Ethiopia" supported by the GEF through the UNDP. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. |

[18]

. Especially from the outlook of indigenous forested areas of Ethiopia mixing of crops in agroforestry like in coffee plots was not assessed. In addition, the inspiring and awareness of community to practice diverse cropping species in the agroforestry to enhance income sources does not exist. According to Cheikh et al

| [4] | Cheikh M., Meine N., Ravi P., and Tony S. (2014). Knowledge gaps and research needs concerning agroforestry's contribution to Sustainable Development Goals in Africa, Current Opinion on Environmental Sustainability. Science Direct, Volume 6, Pages 162-170. |

[4]

, the failure of some agroforestry strategies is related to a lack of integration of different components and system approaches.

Although the literature on agroforestry is vast, the studies on how its benefit relative to the socioeconomic and environmental wellbeing of forest-dependent communities are significantly lacking

| [25] | Pilote K. et al., (2017) Benefits and challenges of agroforestry adoption: a case of Musebeya sector, Nyamagabe District in southern province of Rwanda, Forest Science and Technology, 13:4, 174-180, https://doi.org/10.1080/21580103.2017.1392367 |

[25]

. Recently, in the study area, there was an extension of indigenous forests deteriorating through the practice of extensive agriculture with economic and population growth

| [7] | Ewunetu T and Zebene S. (2018) Tree Species Diversity, Preference and Management in Smallholder Coffee Farms of Western Wellega, Ethiopia. |

[7]

. Moreover, there is problems of diversification of crops and absence of mixed cropping in agroforest area coffee farmland which was indigenous agroforestry practices among many households. Mainly this agroforestry practice is extensive only contain coffee at large. There is an absence of integrating another crop to diversify farming income sources with coffee farming. According to Ramnath et al

| [26] | Ramnathet al (2020). Mixed Farming a Viable Option for Sustainable Agriculture. Food and Scientific Reports, 6(1). |

[26]

, the farming of a single crop in an extensive area is more exposure to climate variability risk. So, there is a lot of information needed to enhance how mixed cropping might adapt agroforestry in the future to climate change in the study area. Hence, based on this gap study was attempted to identify about extent practice of agroforestry as a sustainable practice to achieve both mitigation and adaptation to climate variability in the study area in Ethiopia. It was tried to assess the indigenous experience of the study community in practicing mixed farming in agroforestry areas to improve food security.

1.1. Objective of the Study

1.1.1. The General Objective

The overall objective of this study is to assess agroforestry practice as the response to climate variability and strategy for diversifying farm income in selected woreda, Southwest people region of Ethiopia.

1.1.2. The Specific Objectives

The specific objectives of the study are:

1) To examine Spatiotemporal aspects of agroforestry practice in the selected study areas,

2) To examine the status of farmers’ diversification of agroforestry crops for farm income sources in the study area to adapt to climate-related hazards,

3) To identify the challenges farmers are facing in diversifying agroforestry crop species for farm income diversification and mitigation of climate hazards in selected areas.

The study would answer the following research question after completion:

1) What does the spatial and temporal variation of practicing agroforestry look like in the study area?

2) How does agroforestry practice help farmers to adapt to climate variability-related hazards as a strategy to diversify farm income in the study area?

3) What are the major factors affecting the diversifications of agroforestry practices to diversify the farm crop in selected woreda?

1.3. Significance of the Study

As theoretical striving, this study gives clues or knowledge about the practicing of agroforestry by the study community and its role in climate change adaptation and diversification of live.

The study identified wide-ranging knowledge about the status of diversified agroforestry practice as the technique of climate change adaptation on one hand and its benefit on household income sources and food security in the study area. Thus, it provides valuable information and helps the farmers, agriculture experts, government, NGOs, and any concerned bodies to address gaps in agroforestry practices in general and in the study area in particular. In addition, it helps to understand the diversification of agroforestry practices in climate change mitigation strategies and diversifying income sources. Moreover, the research would be used as a reference for farmers, agriculture experts, and the government to bring sustainable agricultural practices that increase production and suitable environment. The study shows some roads to researchers and the community at large who would like to hunt further scholarships from a new perspective and outlook of the district's household.

The study has conceptual and areal delimitation. The conceptual scope of the study was agroforestry practices as a response to climate hazards and diversification for enhancing household incomes. On the other hand, because of the investigation and data gathering management, and familiarity to the area, the study was limited to Kafa zone, Southwest People region of Ethiopia. In addition to this, the study took into consideration farmers who were practicing agricultural activities a way to diversify crop production for livelihood.

2. Methodology

Kafa Zone is located in the southwestern part of Ethiopia, astronomically between 60 24’ to 80 07’ N and 35º 69′ to 36º 40′ E. The zone is some 460 km southwest of Addis Ababa. Administratively, the zone is found in the Southwest Ethiopia People region and is divided into 12 woredas (the same as districts) administrative classes and five administrative towns. The total land area of the zone is 10,602.7 sq. km.

Figure 1. Locational Map of Study Area.

Figure 2. DEM Map of Study Area.

The study area is dominated by highly dissected rugged topography. About 85% of the landscape is ups and down whereas 5% is flat and the rest area about 10% are plateaus. As

Figure 2 DEM analysis of the area shows altitude range between 500m up to 3305m above sea level. From this, the large area found in the northern, eastern, and central parts of the zone is mainly highland whereas southern parts of zone id dominantly lowland plains. The highest point of the zone is found in Adiyo and Tello woreda (which is above 3000m).

The dominant soil type in the study area is Nitosol. In addition, there are also acrisols in part of Adiyo and Gewata. Moreover, there are also soil types such as Fluvisols, Luvisols, chromic Vertisols, and Cambisols as KZAO of 2020.

Based on the 2007 Census conducted by the CSA (Central Statistical Authority), this Zone was with total population of 874,716, of whom 431,778 are male and 442,938 women; 65,036 or 7.44% are urban inhabitants. According to the Kafa Zone survey of 2020, the total population of this Zone is about 1,228,393 and the total household is 250,692.

For this study, a mixed research approach was used. This approach is a procedure for collecting, analyzing both qualitative and quantitative methods in a study to understand a research problem. Qualitative data of the was obtained by observation, interviews and documents and texts, and FGD. On the other hand, quantitative data have been acquired through questionnaires, and remote sensing data to employ this study. Data were manly obtained using a household survey. Researchers were engaged to collect data on different variables to see how differences in sex, age, educational status, land hold size, and income correlate with the critical variable of interest.

2.3. Sampling Techniques and Sample Size Determination

For this study, sample woredas were selected purposively by considering their agro-ecological zone of the study area. Thus, researchers purposively selected Adiyo, Chena, and Gimbo districts. From these woredas, six small administrative divisions (kebeles here after) were selected purposively based on their agro-ecological conditions which were Kola (lowland or semi- arid), Dega (temperate), and Woina Dega (warm temperate). Moreover, a simple random sampling technique was employed to select household heads using the lottery method.

The total households of in Adiyo district is 30,520, the total households of Gimbo woreda is 24,718, and Chena district has 18,288 households according to Kafa Zone Administrative Office 2020 survey. About 50% of these rural households were taken as the sample unit for the study. These were about 18,381 of farmer households. Then, the size of sample households was determined to be 375 by employing a simplified formula proportion of Yamane

| [34] | Yamane, Y. (1967). Mathematical Formulae for Sample Size Determination. |

[34]

.

Assume N is 18,381 and a 95% confidence level and 5% the desired level of precision

2.4. Data Collection Methods

The primary data were collected from respondents by structured questionnaires. The structured questionnaire was prepared and distributed for respondents in six kebeles found in Chena, Adiyo, and Gimbo districts. Both close-ended questionnaires were incorporated within it. The interview was conducted with model farmers at each kebele and agricultural extension workers to collect in-depth information about farmers’ knowledge of practicing agroforestry in the study area. Six FGDs were also conducted by farmers with diverse ages, knowledge, and sexes which contained six members to evaluate knowledge and performance of agroforestry activities in each kebele. The researchers made an observation in all study kebeles and other forest areas with field trip assistants to see the status of agroforestry practices, and other agricultural activities carried out by farmers.

Secondary data were collected from different officials, satellite imagery, and national meteorology agencies regarding trends in agricultural work, temperature, and precipitation in the study area. Remote sensing data were collected to see land use and land cover change. The land use/land cover change assessment of the study area was collected from Landsat 5 and 8. Landsat Image of 1990, image of 2005, and image of 2021 to cover the periods over 30 years would be used.

2.5. Methods of Data Analysis

Both quantitative and qualitative data were used during this study. The data collected through questionnaires were analyzed quantitatively after being fed into the computer by categorizing, and coding. It was analyzed by using SPSS software. For the quantitative information, the statistical test is conducted at 0.05 α level. The measure of central tendency, chi-square, and ANOVA test were used to summarize and compare the data. On the other hand, the data collected through interview, observation and FGD techniques were transcribed and analyzed using thematic analysis methodology. To see the status of rainfall and temperature variability over 10 years, the coefficients of variability (CV) of the rainfall and temperature were used. The CV of annual and monthly rainfall and temperature was calculated by:

| [12] | Issahaku, A., Campion, B. and Edziyie R. (2016), Rainfall and temperature changes and variability in the Upper East Region of Ghana, Earth and Space Science, 3, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016EA000161 |

[12]

Where, x means annual rainfall in mm, xi - annual rainfall (mm) of the year (i) of a given station, and δ - standard deviation.

Remote sensing data were analysed using ERDAS Imagine version 15. The image was pre-processed and classified by using the supervised image classification method with the help of ERDAS Imagine version 15 software to see LULC change in the study area since the 1990s which fostered the results of the study.

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

This part of the study states the demographic and socio-economics of the respondents. It shows respondents' background information, such as sex, age, literacy, marital status, family size, and major economic activity. These were the most basic data having a closer relationship with the subject matter.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Respondents.

Variable | | Frequency | Percent |

Sex | Male | 346 | 96.3 |

Female | 29 | 7.7 |

Total | 375 | 100 |

Age | 25- 34 | 106 | 28.3 |

35- 44 | 184 | 49 |

45- 54 | 84 | 21.9 |

55- 64 | 1 | 0.8 |

Above 65 | - | - |

Total | 375 | 100 |

Literacy | Can’t Read and Write | 192 | 51.2 |

Primary Education (1-8) | 149 | 39.7 |

Secondary Education (9-12) | 34 | 9.1 |

Total | 375 | 100 |

Marital Status | Single | 14 | 7.7 |

Married | 361 | 96.2 |

Widowed | - | - |

Total | 375 | 100 |

Family Size | 3-4 | 148 | 39.5 |

5-6 | 189 | 50.4 |

7-10 | 38 | 10.1 |

Total | 375 | 100 |

As depicted in

Table 1 96.3% of the study participants were male while the remaining 7.7% were female. This indicates that the majority of the household heads were male. Large proportions of the respondents were between 35 and 44 years old which accounts for 49% followed by the age group between 25- 34 ages with 28.3%. Around 21.9% of them were 44 and 54 years old. This might bring relatively better potential for an economically active population that could contribute to the expansion of agroforestry activity.

The literacy rate of respondents shows 52.9% of participants were joined primary education grades 1-8. However, about 39.7% of respondents could not write and read. Only 16.4% got a secondary school education. Almost 92.5% of study participants were married whereas 3.7% unmarried respondents. This may have a positive impact on agroforestry practices due to the availability of the labor force.

The study area is characterized by a relatively large family size. Accordingly, about 73.4% own family size between 5 and 6 per household. The respondents with family sizes between 3 and 4 members account for 14.7%. Of the total study participants about 18 (11.9%) have a member of a family size between 7 and 10. Having a large family size may initiate high demands for more land for agriculture to support themselves. Such circumstances in turn tend to bring about an expansion of farmland that brings the loss of forests.

The study revealed land hold size of the respondents varies between 1-5 hectares. A relatively large percentage of the respondents' land hold size was 1 to 3 hectares (53%). In addition, respondents with land hold size of more than 5 hectares were 12.3%. The size of land hold affects the kind of farming activities based on farming land. As a study showed 36.8% have stayed in the area for more than 16 years whereas a large share of 46.7% were residents of the area for more than 31 years (

Table 2).

Table 2. Land hold size, and Duration in the Area.

Item | Response | Frequency | Percent |

Land hold size | a hectare | 24 | 6.4 |

1- 3 hectare | 199 | 53 |

>3- 5 hectare | 106 | 28.3 |

Greater than 5 hectares | 46 | 12.3 |

Total | 375 | 100.0 |

Duration of residents in the area | Below 5 years | 16 | 4.3 |

5 to 15 years | 56 | 12.3 |

16 to 30 | 138 | 36.8 |

31 and above years | 175 | 46.7 |

Total | 375 | 100.0 |

3.2. Spatio-Temporal Variation of Agroforestry Activities in Study Area

3.2.1. Land Use Land Cover of Study Area

The land use land cover of the study area shows variability as the data acquired from the Landsat satellite source reveals (

figure 1). The study shows that the main types of LULC in the study area were agricultural land, forest land, settlement area, and rangeland. There have been changes from time to time in these land uses.

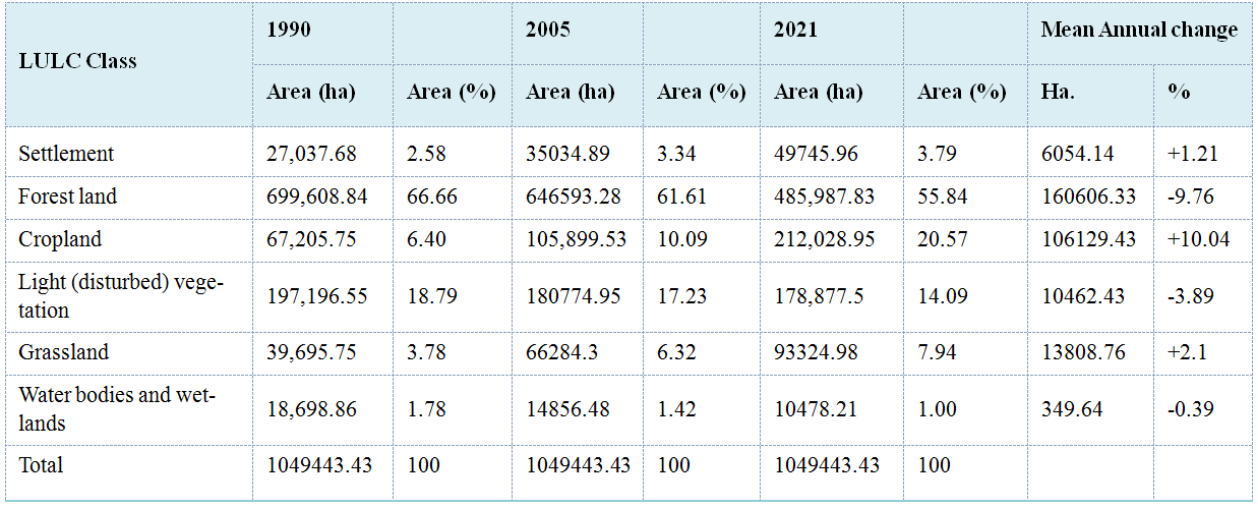

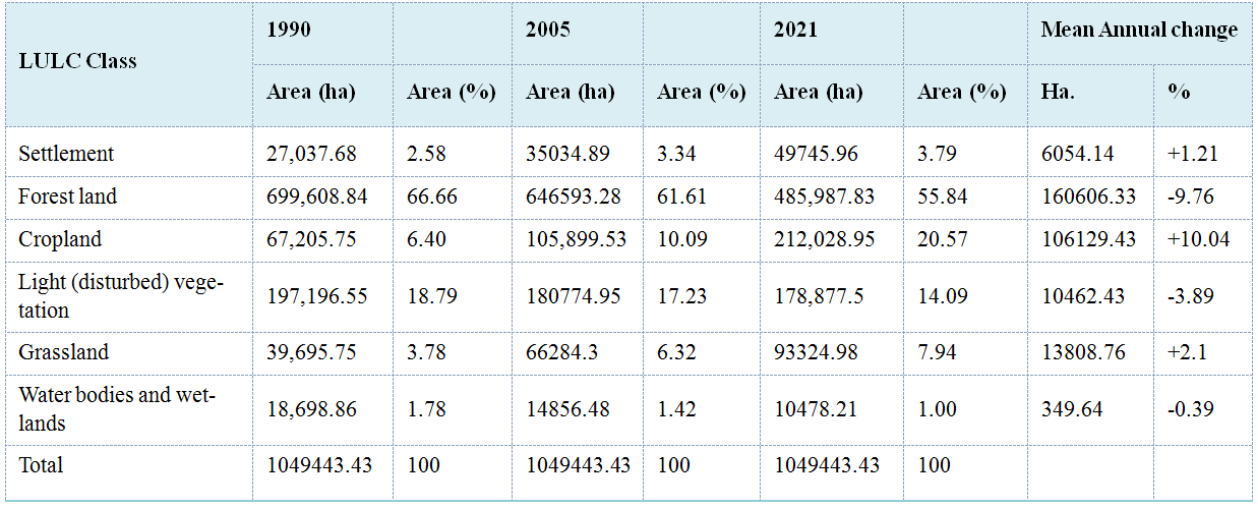

The results of the image classification showed different land use on the total land area was 1049443.4 hectares (ha). Individual class area and change statistics for 1990 and 2021c are summarized in

Table 3.

Table 3. Area statistics and percentage of the land use/cover units in 1990–2021.

Figure 3. Land use land cover change map of 1990 9(a), 2005 (b) and 2021 (c).

The percentage area of each class in 1990 and 2021 showed that forest area had the largest share in 1990 representing 66.35% of the total LULC categories assigned. This class faced a major shift and it was reduced to 55.84% in 2021. The other class that faced a decline during the study period was light vegetation. The area of this class in 1990 was 18.79% (197,196.55 ha) of the total area and in 2021 it was reduced to 14.09% (168,877.5 ha). Furthermore, the size of wetlands and water bodies declined like vegetation and forests. However, the other three classes faced an increase in the total share.

The major increment has occurred in the case of cropland. Its share has increased from 6.40% (67,205.75 ha) in 1990 to 20.57% (212,028.95 ha) in 2021 (

Table 3). So, agricultural area was increased from 6.4% to 20.57% in the study area. The change in the grassland was significantly increased during these study periods. The share in the total area was 3.78% (1416 ha) in 1990 to 7.94% (1579 ha) in 2021.

The study revealed more than 45.0% increase in settlement area from 1990 to 2021 (

Table 3). This value signified the dramatic land cover change in the category of built-up surfaces in particular agricultural lands. In addition, expansion of the already existing urban fabrics through rapid construction of roads, all combined led to continuous expansion of built-up surfaces in the different corners of the study area.

In this study, it was found that there has been approximately a 49% decrease in forest cover in the last 20 years from 1990 to 2021. One of the main reasons for the loss of forests to sparse vegetation can be explained by the immense damage caused by increasing the need for crop production from time to time with increasing population in the study area.

The conversion of dense forests to agricultural land settlement was also expanded. The given data specifically state that the increase in forest area was mainly due to an increase of the need agricultural land and built-up. As Mannan et al

| [17] | Mannan A. et al (2019). Application of land-use/land cover changes in monitoring and projecting forest biomass carbon loss in Pakistan. Global Ecology and Conservation, vol 17. |

[17]

identified in their study the increasing in deforestation leads to the negative impact of soil erosion, high temperature, and dust storms. It would further lead to climatic changes and ripple effects would help in an increase of global warming in the future. Forest that remained undamaged during the study period has existed in all three woredas whereas 9.76% of the forest land degraded indicating the trend towards the deforestation of forest to sparse vegetation each year averagely.

Results indicated that the dense forest present during 1990 had been nearly changed to sparse vegetation by 2021 due to cultivation, and household consumption nearby the residents. The growth of town and expansion of settlement in recent times is also increasing the use of forest areas for agricultural and constructional purposes in this study area. According to UNEP 2004 reports, the wood biomass declining rate is the second highest in the world and ranges from 4 to 6% per year

| [10] | Hassan, Z., Shabbir, R., Ahmad, S. S. et al. Dynamics of land use and land cover change (LULCC) using geospatial techniques: a case study of Islamabad Pakistan. Springer Plus 5, 812 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-2414-z |

[10]

.

3.2.2. Land Use Under Agroforestry

The discussion conducted with FGD shown there is variation of agroforestry activities in the study site within the three agro-ecological zones of study area in size and contents. Hence, in the study areas have different amount of land use under agroforestry. In addition, the agroforestry practice also varies among households according to household land size in its contents. Key interviewees identified that the slope of the land, agro-ecology, cultural experiences, and agricultural policy in the area are the reason for spatial variation in agroforestry practices.

Table 4. Land use under the Coffee and Garden Agroforestry Plot in the study area.

Study site | Agro-ecology | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | F | sign |

Adiyo Woreda | Dega (temperate) zone | 161 | .860 | .757 | 31.885 | .000* |

Gimbo Woreda | Kola (semi-arid) zone | 127 | .569 | .424 |

Chena Woreda | Woina dega (sub-tropical) | 87 | 1.010 | .599 |

Total | | 375 | 0.847 | .681 |

According to

Table 4, there is a significant statistical difference among study areas on the mean hectare of farming plots under agroforestry as the ANOVA test shows (

F2 - 31.885, Sign. (

p)- 0.000). This shows hectares of farm plots used by farmers for garden and coffee agroforestry vary between

Kola (semi-arid climate),

Woina- dega (sub-trpical)

, and

Dega (Temperate) agroecological zones of the study area. The high mean hectare of land use under agroforestry was around 1.01 hectares per household which was found in the Woina- dega agroecological zone. In addition, the second largest mean hectares of the plot of land under agroforestry is Adiya Woreda which is a relatively

Dega agroecological zone.

Thus, the spatial area of agroforestry decreases as the study area’s agro- ecology changes from Woina- dega to dega and kola. The study results shown in the lowland (kola) part of Gimbo woreda the land use under agroforestry is low compared with Chena woreda and Adiyo Woreda Kebeles (i.e. 0.569 mean hectare). This may be due to low coffee plot in The Kola area. Thus, the variation may occur due to coffee plot size in the Dega and Woina-dega than Kola part of Gimbo.

On the other hand, some diversity was observed on the basis of species mixing status in garden agroforestry. As

Figure 4, along backyard land use, the diversity of crop species in the agroforestry plots is higher in the

Kola agro-ecological of Gimbo woreda than in Adiyo and Chena woreda base upon the respondents replied.

Figure 4. Level of Home Garden Crop Species Diversity in Kafa Zone.

In Gimbo woreda, about 52.9% of respondents have more diversified home garden plots. As the FGD conducted in Shambo Sheka and Yeretechit kebeles indicated, there is mainly a mixing of bananas, mango, avocado, orange, coffee, and papaya with different indigenous and non-indigenous trees along their home as garden agriculture. On the other hand, in Chena woreda, the diversity of garden farming species is mostly dominated by inset, avocado, and coffee. The garden agroforestry in Adiyo woreda and Chena districts is less diversified when compared with Gimbo. In Adiyo garden is highly dominated by insets and around some homes, there are also coffee and avocado with annual crops.

The diversification of the home garden species varies among different study

woreda based on their agro-ecological zones. As the above figure shows, there are mango, avocado, coffee, and eucalyptus trees in the garden at Gimbo (

Figure 5). Hence, more diversified crop species around the home garden plot is the Gimbo kola area where low species crop diversity along Adiyo

woreda with

Dega agro-ecological climate zone.

Figure 5. Garden agroforestry in Gimbo woreda.

3.2.3. Kinds of Dominant Agroforestry Practicing in Study Area

There is variation on kinds of agroforestry widely practiced in the study area due to the agro-ecology, wildlife effects, socio-culture and other factors. Coffee farming and home garden agroforestry were the main extensive agroforestry practicing. Discussion with FGD disclosed as many of study communities have coffee and home garden agroforestry plots productions type of indigenous agroforestry. The informant described cultivating a garden separately with perennials and annual crops was common and the indigenous activities among many households in the study area. Most households have home garden agroforestry with variation in size cropped with coffee, inset, banana and avocado dominantly. In addition, the farmers are engaging in raising animals in addition to this crop farming.

Table 5. Types of agroforestry dominantly practiced.

| Study site agro-ecology | Total | Chi-Square (χ2) | Sign. |

Adiyo Woreda (Dega zone) | Gimbo Woreda (kola Zone) | Chena Woreda (Woina dega) |

Coffee cultivation with Perennial wood | N | 34 | 26 | 64 | 137 | 23.616 | 0.000* |

% | 25.4 | 27.6 | 75.9 | 34.7 |

Annual crop with sparse perennials vegetation and wood tree | N | 68 | 29 | 6 | 95 |

% | 39.8 | 15.7 | 6.9 | 25.3 |

Home garden agroforestry only | N | 59 | 72 | 17 | 148 |

% | 34.8 | 53.5 | 17.2 | 39.5 |

According to a Chi-Square test result at a

p-value less than 0.05 there is significant difference among different agroecology (

Table 5). The difference in the agro-ecology of has effects on types of agroforestry dominantly practicing

| [19] | Nair P. (ed.) (2007) Agroforestry Systems in Major Ecological Zones of the Tropics and Subtropics. International Council for Research in Agroforestry (ICRAF), Nairobi, Kenya. |

[19]

. Hence, there are differences between the study

woredas on the basis of agro-ecology. In

Woina-dega agro-ecology, which is in Chena

Woreda, coffee agroforestry with perennials wood has been more importantly performing among 75.9% of study participants whereas the

Kola climatic zone, found in Gimbo

Woreda, were largely performing backyards agroforestry as 53.5% of the respondents replied from the study site. On the other hand, the kind of agroforestry activities that are dominantly on-going in Adiyo is the annual crop with wood trees needed for a variety of roles at large (39.8%). However, extensively about 34.8% of the study population practices mainly garden agroforestry in the study area.

In addition to community experience and agroecological effects, agroforestry practices need knowledge from experts’ agriculture and forest for application for better adaptation to climate change. Key informants discussed that the provision of knowledge of agroforestry from experts is low. Large numbers of communities were trying on coffee farms expansion which were sustained under forest land with indigenous coffee since early times. However, there has been an incline to upsurge annual crop farming over time since recent. In addition, farmers are eager to expand exotic trees used for commercial purposes to indigenous plants. Today, tree species such as eucalyptus, and grevilleas are planted along a given plot and roads on many households’ farmland.

On the other hand, FGD results shown in all study sample home-garden activities became motivated by extension workers among all communities with farming manly inset, vegetables, and fruits. In addition, recently the expansion of the planting of avocados has grown. They discussed that supplementary vegetables, fruits, and spices are recently emerging in the home gardens area. Recently, the planting of varieties of vegetables in home gardens was widely mobilized in all study woredas as agricultural officers discussed.

Figure 6. Eucalyptus and Tid trees with home garden perennial crops in Gimbo.

As a study conducted by Kumar and Nair

showed, the cultivation of different crops in home-gardens is regarded as a strategy of farmers to diversify their subsistence and cash needs. Diversification also helps to stabilize yield and income in cases of incidences of disease and pests, and market price fluctuations. Although home garden agroforestry has such positive impacts on households’ livelihood sustainability, the cultivation of home gardens diversified crops in the study area in a very small area as this study showed.

Key informants' also discussed indigenous communities have good knowledge of cultivating in wood trees and they do not clear big trees totally from farming land which is passed from forefathers. Thus, there is indigenous knowledge of agroforestry practices in the community. The community has different ways of tree conservation approaches such as moral values; sacred places; raw materials for home; and traditional medicine. Thus, there is extensive annual cropping land in Adiyo with sparse trees.

The other spatial variation of agroforestry practice observed in the study area was examined concerning land use and land cover with wood trees. There is no significant association among the study sites regarding the high frequency of woody trees in the farming plot with the difference in agroecology (

Χ2 (2)> = 4.923,

p - 0.076). As informants’ discussion, the frequency of availability of trees in farm land is high in coffee land in all study sites in all agro-ecological climates. According to 47.1% of respondents from Chena Woreda, there is a high frequency of tree species in coffee farming plots (

Table 6).

Table 6. The kind of land use with conserved diversified woody trees with crops.

Item | Response | Study site agroecology | Total | Chi-square test Χ2 | Sign. (p) |

Adiyo Woreda (Dega) | Gimbo Woreda (Kola) | Chena Woreda (woina Dega |

Diversity of tree species in farm plot | In the coffee forest land | N | 140 | 76 | 41 | 257 | 4.923 | 0.076* |

% | 87.2 | 59.8 | 47.1 | 68.5 |

Home garden | N | 15 | 30 | 20 | 65 |

% | 9.1 | 23.6 | 22.9 | 17.3 |

on annual farming land | N | 6 | 21 | 26 | 53 |

% | 3.7 | 16.5 | 29.9 | 14.1 |

Total | N | 161 | 127 | 87 | 375 |

% | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Generally, the most variety of tree species is found in the coffee plot unit as 68.5% of respondents replied. Whereas annual agricultural land and home garden cultivation areas have a small variety in terms of wood tree species. As the FGD and observation results showed the average density of trees with a height above 2m on the studied agroforestry plot varied between the

kebeles. The informants stated that the wood trees frequently exist in Adiyo Woreda (

Dega kebeles) and Chena Woreda (

Woina dega agroecological zone

kebeles) than the

kola climatic zone in Gimbo Woreda. The most abundant species among all shade tree species were cordia Africana (

Wanza) (around 4-7 trees per farm) followed by, Albizia gummifera (Sasa), Croton macrostachyus (

Bisana), Ekebergia capensi (

Somb), Carissa edulis (

Agamsa),

Kermo, Albizia schimperiana (

Tikur Incat) and ficus vasta (

Warka). The diversity does not show great variation when compared with the study conducted in the Sidama zone by Tesfaye et al

| [32] | Tesfaye A. & Frank S., Wiersum, K. and, Frans, B. (2013). Diversity, composition, and density of trees and shrubs in agroforestry home gardens in Southern Ethiopia. Agroforestry Systems. 87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-013-9637-6 |

[32]

on diversity, composition, and density of trees and shrubs in agroforestry home gardens which was the number of tree species per farm varied from 4 to 55 with an overall average of 21.

As respondents evaluate their annual crop land in terms of wood trees in it, there is unevenness of frequency available trees across the study woredas. In Gimbo woreda where its climate is kola the density of trees in the annual crop is very sparse at 63.1%. However, more frequently available trees are found in annual crop land in study sample Adiyo which is most probably its agroecology (

Figure 7).

All FGD participants agreed on the existence of trees in the farm land among all the households. They elaborated that people have not cleared large trees even from their annual crops lands. Specifically, trees used for home materials preparation are mostly conserved on the same field with annual cropland. However, currently, there is an initiation coffee planting in the community. Such activity is good for increasing the density and diversity of wood trees from time to time in the place. In addition, there is also an increase in fruit, inset, and coffee cultivation at garden plots in Chena woreda with the help of the agricultural office as interviews with office officers showed. The guidance and advice of agricultural experts working as agricultural extension workers is also viable in this woreda.

Figure 7. Frequency of wood tree in annual crop land.

Table 7. The status of practicing agroforestry among households.

| Education Background | Total | Chi-Square Tests | Sign. |

Cannot write and read | primary school | secondary school |

Status of practicing agroforestry across their education level | Very low | N | 49 | 28 | 4 | 81 | 6.214 | 0.421 |

% | 25.5 | 18.8 | 11.8 | 21.6 |

Low | N | 83 | 64 | 12 | 159 |

% | 43.2 | 42.9 | 35.3 | 42.4 |

Moderate | N | 35 | 36 | 8 | 84 |

% | 18.2 | 27.5 | 23.5 | 22.4 |

High | N | 25 | 21 | 10 | 56 |

% | 13 | 14.1 | 29.4 | 14.9 |

Total | N | 192 | 149 | 34 | 375 |

% | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

According to

Table 7, the study revealed the level of practicing agroforestry in the study area is not associated with educational status as

Χ2 (2) > = 6.214, Sign. (

p) - 0.421. This shows that participating in agroforestry activities is the same to some extent among all respondents. The key informants revealed that there is indigenous experience among the community which is a determinant for the expansion of practicing agroforestry. The agricultural extension workers are also initiating the farmers with working garden agriculture. Most respondents (64%) have low status practicing this agroforestry.

Contradictory to this study result, Oino and Mugure

| [22] | Oino P. & Mugure A. (2013), Farmer-Oriented Factors that Influence Adoption of Agroforestry Practices in Kenya: Experiences from Nambale District, Busia County. IJSR: 2319-7064, (450-456). |

[22]

conducted a study on agroforestry and they stated that the level of education has a strong relation with the household afro-forestry exercise and based on their analysis they concluded education of the household head influences the decision to adopt agroforestry practices in their study area.

Table 8. Major forests preferred by individuals on land holds around their home and for coffee shade.

Local name | Scientific name | Uses of tree |

Wanza | Cordia africana | Critically, used for timber and preparing home tools, coffee shade |

Giraw | Albizia gumifera | Increasing soil fertility, shade of coffee, hive keeping. |

Suspaniya | | For coffee shade |

Sasa | Pygeum africanum | Coffee cover, used for caw feed |

Bisana | Croton Marostachyus | Used for coffee shading, |

Warka | Ficus vestsa | For coffee shade and livestock foods |

Birbira | Pygeum africanum | Coffee shade and shade for cattle |

The conservation practice for these indigenous trees was based on two important uses of forests as the table above shows. Accordingly, the first main purpose that the community conserves in the plot of land is related to the service of shade for coffee, vegetables, and fruit. The second role of indigenous trees in the area is their function in economy and health (

Table 8). For instance, the economic value is related to agroforestry such as increasing soil fertility, timber, and hive keeping. They only cut trees that are too old while using it. In addition, do not clear trees even if it is a very dense place. Sparsely available wood trees are not cut down based on indigenous land use.

3.3. Diversification of Income Sources Through Agroforestry Practices

In a different country, there are different strategies that the government use to enhance the livelihood of farmers. For instance, Sobola, Amadi & Jamala

| [30] | Sobola, O., Amadi, C., Jamala, Y. (2015). The Role of Agroforestry in Environmental Sustainability. IOSR Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science (IOSR-JAVS), Volume 8, 5, I, PP 20-25. |

[30]

stated that there are different farming enhancement strategies such as planting of drought-resistant varieties of crops; crop diversification; change in the cropping pattern and calendar of planting; mixed cropping; improved irrigation efficiency; adopting soil conservation measures that conserve soil moisture; planting of trees and agroforestry.

The enhancement of farm income in rural areas depends on the focus of the agricultural policy of a country. In the study area, agricultural activities that are ongoing to improve farmers' income sources were different among households as informants discussed. However, the status and focus of enhancing agroforestry practices was low.

The shown in above table, the condition of diversified agroforestry practices is low as the aspect of the strategies of farmers using diversifying income sources from farm income. Most number of the respondents is the use of fertilizer and conservation of commercial trees with crop as a general. Conserving commercial trees on their farm was one of the aspects of agroforestry farming that is improving farm income. This is highly practiced in Adiyo and Chena. There is a significant difference between the sample kebeles on their strategies of farming income diversification. So, there is the effect of agroecology on the strategies for farm income increasing.

However, in Gimbo Woreda the ways farmers diversify income from farms were more or less related to agroforestry which is the expansion of fruit and vegetables on home garden farming and in farm plots (40.2%). Whereas Adiyo and Chena Woreda are mostly trying to increase farming income through the use of fertilizer and planting trees which is focused on annual crop production from time to time (

Table 9) However, as the above table shows the communities are not attempting to diversify species within the same plot and farming other spice under coffee land were very low. It is below 5%.

Table 9. The methods of farm income sources diversifying among study community.

Mechanism | Agroecology of Study Sample | Total |

Adiyo Woreda (dega zone) | Gimbo Woreda (kola zone) | Chena Woreda (woina Dega) |

Double cropping on the same farmland | 42 (26.1%) | 15 (11.8%) | 32 (35.9%) | 89 (23.7) |

The use of fertilizer | 128 (79.5%) | 26 (20.5%) | 34 (18.1%) | 188 (50.1%) |

Conserving indigenous trees has economic value | 105 (65.2%) | 36 (28.3%) | 49 (25.7%) | 190 (50.7%) |

Expanding home garden farming | 42 (26.1%) | 51 (40.2%) | 44 (32.1%) | 137 (36.5%) |

Cultivating another crop in coffee lands | | 7 (5.5%) | 10 (11.49%) | 17 (4.5%) |

Table 10. The knowledge participants about the influence of agroforestry on improving income.

| Education Background | Total | Chi-square test | Sign. |

cannot write and read | primary school | secondary school |

Agroforestry as a sources of additional household income | Yes | N | 150 | 131 | 34 | 110 | 5.507 | .138* |

% | 78.1 | 87.9 | 100 | 63.2 |

No | N | 42 | 18 | - | 64 |

% | 21.8 | 12.1 | - | 36.8 |

Total | N | 192 | 149 | 34 | 174 |

% | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

The community knowledge about the effect of agroforestry on household overall income/benefits is quite necessary for the expansion of agroforestry practice.

Table 10 indicates similar understanding of the community on agroforestry as diversifies household income. Hence, there is the same understanding among the study respondents regarding the influence of agroforestry in improving income without to their educational status (

Χ2 > = 1.821, Sign. (

p) - 0.656). Almost all community accept that agroforestry has a significant role in household income. This is due to the reason that the even though for subsistence and basic survival there is agroforestry indigenous activity of the area.

As Lasco (2014)

| [15] | Lasco R., Delfino R., Espaldon M. (2014). Agroforestry systems: helping smallholders adapt to climate risks while mitigating climate change. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 5(6): 825-833. |

[15]

identified the recognizing of agroforestry as ecologically base natural resource management system that diversifies and sustains production among the community has an impact on agroforestry implementation. On the other hand, agroforestry adoption has contributed to the increase of farmers’ income.

Hence, the acceptance of the community on agroforestry needs awareness about the main function of the kind of farming that has an overlapping purpose in economic and environmental proceeds. As the key informants discussed the benefit is related to the income of coffee production. Rather the consideration of trees as environmental and economic value is not well understood among the community. The agricultural experts of the kebeles state that people conserve wood trees mainly in their coffee farm plots for shading. The community does not clear wood trees from coffee plots and farmland despite there being a selection of the types of trees mostly accepted for the shading of coffee.

3.3.1. Status of Ecological and Economic Trees in Agroforestry Land

Agroforestry can achieve and maintain conservation and fertility roles when it conserving the perennial wood trees as the resource base. As discussed with key informants, there are some selected tree species used for coffee shade and other agricultural production conserved by the farmers such as Cordia Africana, Albizia gummifera, ficus vasta, eucalyptus and grevillea. The lower-layer tree species have been cleared from coffee plots for its blossoming.

Table 11. The mean number of Indigenous tree species found in the farm plot.

Sample woreda | Agro-ecology of study kebele | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | One Way ANOVA (F) | Sig. |

Adiyo Woreda | Dega (temperate) | 161 | 10.67 | 1.18357 | 6.869 | 0.03* |

Gimbo Woreda | Kola (semi-arid) | 127 | 6.24 | 1.09023 |

Chena Woreda | Woina- dega (sub-tropical) | 87 | 11.20 | 1.98589 |

Table 11 presents the mean number of species of indigenous trees mostly the choice of the farmers. The residential area has a significant effect on the variety of wood trees in agroforestry areas. There is a significant difference among study areas in the number of tree species favored by farmers to use for coffee shadow as One Way ANOVA test indicates (

F2 is 6.896 and sig is 0.03). Large numbers of indigenous tree species are found in Adiyo Woreda which is about an average of 10.6 species and small species at Gimbo Woreda (6.2 species average) in coffee plots.

Predominantly, the number of wood and shrub species in coffee farms was lower than that of the forest reserve in this study area. The community does not allow the growth of shrubs mainly in coffee and other crops. Likewise, a study conducted by Correi et al.

indicates that tree species diversity was found to be higher in forest area than in coffee farms area in their study area.

The sustainability of agricultural output and reduction of climate variability impacts of agroforestry rely on the diversity of crop and tree species on farmland. This study identified that a considerable number of tree species are being managed and conserved in coffee farms at large and gardens plot and annual farmland at small or rare. As the key interviewees stated more than 5 to 10 tree species are preferable for coffee shading and in home garden areas. According to this discussion, however, compared to coffee farms in other part of the world, the number of tree species observed in the study area appears to be lower. For example, as study of Ewunetu and Zenebe

| [7] | Ewunetu T and Zebene S. (2018) Tree Species Diversity, Preference and Management in Smallholder Coffee Farms of Western Wellega, Ethiopia. |

[7]

identified in west Wollega zone of Oromia, the species richness of studied coffee farms is small like this study. On the other hand, they identified small tree species is found in coffee plots similar to this study.

3.3.2. Status of Agroforestry in Adapting Climate Variability in the Study Area

Agroforestry gives more flexibility and benefits from the environmental and socio-economic perspective during this current time when changing climatic situations are inevitable everywhere. One of the best characteristics of agroforestry systems is the ability to stabilize ecosystems

| [16] | Lema, M. A. and Majule, A. (2009). Impacts of climate change, variability and adaptation strategies on agriculture in semi-arid areas of Tanzania: The case of Manyoni District in Singida Region, Tanzania. African Journal of Environmental Science and (1)Technology. 3 (8), Pp. 206-218. |

[16]

. Given the potential economic returns, agroforestry systems, as a long-term investment and adaptation strategy to uncertainties of changing climate can minimize risk by simply diversifying the products of farming households

| [3] | Antonio S. et al., (2020). A Review of the Role of Forests and Agroforestry Systems in the FAO Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) Programme. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11080860 |

[3]

.

Table 12. Temperature and Rainfall coefficient of variance in the study area.

| Station | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | CV |

Rainfall | Chena | 1647.9 | 1306.9 | 1153.2 | 1277.1 | 1042.4 | 1055.4 | 1351.6 | 1186.1 | 1403.2 | 1222.6 | 24.912 |

Gimbo | 1258.05 | 1198.8 | 1286.6 | 1249.9 | 1495.2 | 1271.3 | 1249.3 | 1107.3 | 1224.5 | 1106.9 | 32.53 |

Temp. | Gimbo | 18.05 | 19.4 | 20.3 | 20.6 | 19.8 | 22.3 | 22.8 | 22.5 | 19.9 | 20.16 | 5.08 |

Chena | 17.6 | 18.1 | 19.4 | 19.6 | 18.9 | 19.4 | 20.4 | 20.7 | 18.8 | 19.7 | 2.85 |

Source: National Metrology Agency, 2022

The CV of rainfall and temperature is high in the lowland part of Gimbo Woreda along the Gojeb area as the data acquired from the metrology agency. The rainfall variability is 24.912 in Chena and 32.53 in Gimbo (

Table 12). There is high variability of temperature in Gimbo which is 5.08

oc. However, in Chena, the coefficient of variability of temperature is 2.85

oc. As a result, it needs the implementation of agroforestry in this area to tackle the problem of climate on agricultural production rather than enhancing single crops. Thus, agroforestry adoption in all study areas will be important in improving their income status and enhancing their livelihood activities within such kind of climate variability problem.

Another significant base for the sustainability of agroforestry production is the diversification of kinds of crops during this climate change. A single type of cropping as agroforestry practices also faces many different problems due to current climatic change effects. So, the sustainability of agroforestry is dependent on the diversification of the crop under agroforestry. According to Ramnath et al

| [26] | Ramnathet al (2020). Mixed Farming a Viable Option for Sustainable Agriculture. Food and Scientific Reports, 6(1). |

[26]

, the farming of a single crop in an extensive area is more exposure to climate variability risk and is not sustainable in yield.

Mixing different crop species or varieties can play many roles in reducing plant diseases, reducing the spread of disease, and modifying the environmental conditions of crop plots so that they are less favorable to the spread of certain diseases as discussions with key experts showed. Thus, the farmers need to experience and strengthen the mixing of varieties of crops in agroforestry practices.

Table 13. Status of Agroforestry Diversification for Income Source Enhancement and Climate Variability adaptation.

| Study Site | Total | χ2 | p |

Adiyo | Chena | Gimbo |

Mixing different crops in agroforestry land use | Low | 65 | 22 | 39 | 122 (32.5%) | 2.898 | .575* |

medium | 77 | 46 | 65 | 188 (50.1%) |

high | 19 | 19 | 23 | 65 (17.4%) |

Cropping spices and fruits in coffee land | Low | 73 | 42 | 95 | 210 (56%) | 5.973 | .201* |

medium | 87 | 45 | 32 | 165 (43.7%) |

high | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3%) |

Cropping inset, banana, avocado, mango, orange, papaya, spices, lemon, and others at garden | Low | 116 | 19 | 15 | 150 (40%) | 22.354 | .000 |

medium | 32 | 49 | 66 | 147 (39.2%) |

high | 13 | 19 | 46 | 78 (20.8%) |

The status of agroforestry practices for farming income increasing | Low | 56 | 33 | 9 | 98 (26.1%) | 39.478 | .000 |

medium | 73 | 20 | 63 | 156 (41.6%) |

high | 32 | 34 | 55 | 121 (32.3%) |

Table 13 illustrate the status of the study community regarding promoting diversification of crop production species in agroforestry areas is low. All study sites have the same level of mixing practice as above table (

2- 2.898 and

p-.575). Therefore, residential sites didn’t show the major effect on respondent species diversification in agroforestry. All respondents have a similar status which is low diversification of agroforestry crops. Thus, the sustainability of agroforestry concerning income diversification is less and low ability to climate variability tackling. About 122 (32.5%) have very little practice in mixing and diversifying different crop species in their agroforestry farming. Around 188 (50.1%) of the study respondents replied that they have some involvement in mixing some crops in their garden land use.

The results of FGD confirms, that the community has very little idea of diversifying the variety of crops in coffee plots from agricultural experts. Even though the diversification is more focused on different land uses, different communities have low concepts in the case of farming different spices and fruit together. So, there is a significant low sustainability of production during the time of climate hazards in this area due to the low diversification of other species. However, they state that agroforestry provides the farmers with a large number of alternatives to agricultural, forestry, and horticultural crops and thus gives more income to the farmers per unit of land than monoculture in sustainable ways.

The experience of cropping spices and fruits in the coffee plot outside of the garden was low as shown by 210 (56%). Even there is no difference according to the difference in study site as the chi-square test of association is p>0.05 (2- 5.973 and p-.201). Thus, indigenous coffee agroforestry in the study area is not diversified which ensures sustainability for the mitigation of climate variability problems.

In the garden field, the level of cropping of different fruits and vegetables such as inset, banana, avocado, mango, orange, papaya, spices and lemon together is small among 150 (40%) of the total study participants. Nevertheless, it is more practiced in Gimbo and Chena when compared according to the study site. Thus, the study site has an effect on farming of mixed different fruits, spices, and vegetables together on the same field as shown by the chi-square test (2- 22.354 and p-.000). The increment of the practice of agroforestry for form income in the study area is medium as it is selected by 156 (41.6%) of study respondents. It however vary between study site based on chi-square test result (2- 39.478 and p-.005).

3.4. Major Challenges in Agroforestry Practice Diversification

According to the result of the study, the only extensive agroforestry practice in the area nowadays are ongoing under different constraints. The activity of home garden agroforestry is low in many parts of the study area. This is related to different restrictions that occur as a challenge in agroforestry. It seems that farmers were traditional to adopt more tree planting, given the appropriate conditions. The lack of significant knowledge among farmer on crop diversification, market inaccessibility, wildlife damage, effect of climate (variability of crops on different climatic condition), agricultural policy focus and low support of government were some challenges affecting the practice of diversified agroforestry that enhance survival of community during climate variability.

3.4.1. Knowledge and Understanding Related Challenge

One of the biggest challenges in enhancing income sources from agroforestry in the study area is low awareness in diversifying crops in the agroforestry area. Key interviews are described as there is quite eager and initiation in agricultural activities from the concerned body to increase production and productivity. However, focus is on extensive annual crop farming among all study areas. This is one of the major challenges where the community has low awareness and information on enhancing diversified production of agroforestry.

Table 14. Knowledge and Awareness of the community on agroforestry diversification.

Variable | Categories | Knowledge and understanding | χ2 | p |

Yes | No |

Age | 25- 34 | 45 (12%) | 61 (16.3%) | 0.195 | 0.778* |

35- 44 | 71 (18.9%) | 111 (29.6%) |

45- 54 | 33 (8.8%) | 51 (13.6%) |

55- 64 | | 3 (0.8%) |

Residential area | Adiyo | 30 (8%) | 131 (34.9%) | 6.685 | 0.035** |

Chena | 40 (10.7%) | 47 (12.5%) |

Gimbo | 79 (21.1%) | 48 (12.8%) |

Education Background | Cannot write and read | 68 (18.1%) | 124 (33.1%) | 6.839 | 0.033** |

Primary school | 63 (6.8%) | 86 (22.9%) |

Secondary school | 19 (5%) | 15 (4%) |

The awareness regarding the concept of agroforestry and knowledge to diversify different crops under agroforestry area has no association with the age of respondents according to

2- 0.896 and

p- 0.778 (

Table 14). Thus, there is a similarity among all respondents among different age group of the respondents on their knowledge of diversification of agroforestry. Their knowledge of the agroforestry system which is suitable for reducing the effect of climate variables on farming was one problem of expanding agroforestry practices. About 59.5% of respondents have replied as they have no knowledge of it.

The FGD shows the cultural food experience of the country is more or less highly dependent on cereal crops. Thus, the availability of large quintals of cereal crops is more necessary for livelihood than expanding fruit and vegetables. This leads the household the use land extensively for cereal crops rather than agroforestry.

Conversely, the level of knowledge of agroforestry crop mixing has an association with the agroecology of the study area at p is 0.035. This shows there is a difference among households according to their area of residence in the Kafa zone. More awareness of diversification of agroforestry exists in Gimbo (62.2%) and Chena (45.9%) woreda. In addition, the level of education also has influenced the knowledge of diversified agroforestry practice in the study area. The more educated were more understanding than the low educational status respondents. As a result, there was an association of knowledge of agroforestry practice with the level of education of the respondents at p< 0.05 (2- 6.839 and P- 0.033).

3.4.2. Impacts of Market Inaccessibility, Climate-Related and Wildlife Destruction

Another of the most vital challenges related to the practice of diversified agroforestry are market inaccessibility, climate conditions, and the problem of wildlife. Near to their home there are annual cropping lands extensively in the study area. As the interviewees elucidated the activities of another crop in coffee agroforestry land is impossible in the case of fruit and vegetable as a result of the destruction of wild animals like apes, monkey, and porcupine.

Moreover, as the FGD participants describe, the common kind of agroforestry is mainly coffee and garden. This agroforestry needs a keeper if there is farming of other species under it because it is affected by wild animals. Even wild animals are mainly affecting coffee during its maturity. Furthermore, there is a low status of the community in farm spice with coffee is low for coffee plots found after annual cropland and along the edge of the valley.

Figure 8. Major obstacle to the diversified Agroforestry practice.

As indicated by

Figure 8, the diversification of agroforestry is challenged by market inaccessibility, wildlife damage, and unsuitability in some areas for some farm fruits and vegetables. Above 64% of the respondents strongly agreed on the inaccessibility of a market for fresh fruit in their areas. Most kebeles are far from the main road. In addition, the transport accessibility is low in the case of some kebeles in study woredas.

In addition, there is a very severe problem of wildlife destruction regarding to planting of different fruits and vegetables as 52.9% of respondents strongly agreed. Similarly, about 12.2% of respondents agree that there is an unsuitability of climate in the area regarding cropping variety of vegetation and fruit. The climatic condition of the study is different within each study area (See

Figure 6). Hence, species diversification especially in garden farming is limited by the climate of the area. The ten-year climate conditions of two study woreda show high variability of climate (

Table 12).

According to the Agroforestry Network

| [1] | Agroforestry Network, 2018. Scaling up Agroforestry: Potential, Challenges and Barriers. A review of environmental, social and economic aspects on the farmer, community and landscape level. Stockholm: Agroforestry Network and Vi-skogen. |

[1]

, the status of agroforestry is a widespread practice in the world, and its availability is increasing at national and international levels. The study identified a number of challenges that prevent a broad-scale implementation of agroforestry practices. They mainly include inefficient markets, unclear land rights, limited access to knowledge and finance, and a lack of inter-sectorial collaboration. Hence, many of these barriers are also observed in the study area. The knowledge of the community is low about practice of diverse agroforestry crop species as discussion with FGD participants presented. For that, there is inaccessibility of the market especially for remote

kebeles in the case of vegetable and fruit production.

3.4.3. Challenges Agriculture Policy, Low Government Support and Access to Seedlings

During this study, the need for credit or government-provided incentives for support and seedlings were identified as major constraints by 85.03% of the households surveyed. The participants of FGD and interview stated the availability and access to seedlings of different fruits and vegetables is very low in the area. Thus, most of the time single agroforestry is common in many parts of the study woredas especially since there is an initiation of coffee agroforestry. Similar to this study, according study conducted by Oke et al.

| [21] | Oke, O. S. et al. (2023). Involvement of selected arable crop farmers in agro-forestry practices in Ekiti state, Nigeria. UNIZIK Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 2(1). |

[21]

showed constraints to agroforestry implementation identified the need for credit or government-provided financial incentives, and seedlings all were identified as constraints by 84% or more of the farmers surveyed.

Table 15. Challenges related to policy, capacity building, and support from the government.

Items | Response | Education Background | Total | χ2 | p |

cannot write and read | primary school | secondary school |

Low support of policy and program of agriculture to agroforestry as primary activities | Yes | 150 | 106 | 26 | 282 (75.2%) | 2.620 | 0.297* |

No | 42 | 43 | 8 | 93 (24.8%) |

Constraints of Capacity building and field demonstrations by training farmers about adopting agroforestry | Yes | 160 | 111 | 23 | 294 (78.4%) | 3.472 | 0.748* |

No | 32 | 38 | 11 | 81 (21.6%) |

Constraints of support and subsidies for seedlings as support by agroforestry species | Yes | 168 | 126 | 30 | 324 (86.4%) | 6.785 | 0.341* |

No | 24 | 23 | 4 | 57 (13.6%) |

The other challenge identified in the study area was the focus of agriculture programs and practices at the woreda level. According to the respondents, the first focus of agricultural policy is related to extensive single crops (75.2%) (See

Table 15). This may initiate the expansion of annual crop production to be the concern of community. Respondents have a similar on the idea of the existence of low agricultural policy that supports agroforestry (χ

2 = 2.620 and

p= 0.297

). This means all respondents have the same awareness without variation in level of education as agricultural policy was low support to agroforestry.

This idea is similar to the study of FOA

| [8] | FAO (2013). Advancing Agroforestry on the Policy Agenda: A guide for decision-makers. Agroforestry Working Paper no. 1, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. |

[8]

on the main challenges for agroforestry results as agricultural policies often offer incentives for agriculture that promote certain agricultural models, such as monoculture systems, and tax exemptions are usually aimed at industrial agricultural production. Again agricultural practices are favoring credit terms which are granted for certain agricultural activities but hardly ever for trees are also discouraging agroforestry adoption.

Kaonga

| [13] | Kaonga, M. L. (2012) Agroforestry for Biodiversity and Ecosystems Services: Science and Practices. In Tech, Rijeka. https://doi.org/10.5772/2100 |

[13]

identified in his study as the policy and program play an important role in differentiating countries and regions that have benefited greatly from agroforestry from those that have not. Where these have been absent or contested, tree planting and management by farmers have been limited. In addition, policies related to tree germ-plasm reproduction and dissemination are important in facilitating the expansion of agroforestry. In addition, similar to this study research conducted by Pilote et al

| [25] | Pilote K. et al., (2017) Benefits and challenges of agroforestry adoption: a case of Musebeya sector, Nyamagabe District in southern province of Rwanda, Forest Science and Technology, 13:4, 174-180, https://doi.org/10.1080/21580103.2017.1392367 |

[25]

in Rwanda indicated the primary challenge of agroforestry practices was lack of capital as it was ranked high among the limitations preventing farmers from fully adopting agroforestry practices.

Regarding the farmers' training and building capacity in agroforestry, there was a low in the study area.

Table 16 shows there is no association between the educational status of respondents on the building of capacity knowledge of farmers about agroforestry in the study area (χ

2= 3.472 and

p= 0.748

). The level of the capacity for knowledge and building farmers’ capacity to enhance agroforestry practice was constrained. About 78.4% of the study participants informed the other challenge in agroforestry practice was absence of capacity building and field demonstrations by training farmers about adopting agroforestry.

On the other hand, there is also little attention from governments in the case of supporting the community in adopting diversified agroforestry. There is a similar response among all educational levels on the low availability and support of the government regarding seed access (

p= 0.341) for home garden species diversity and agroforestry expansion. About 86.4% of study participants agreed that there were constraints of government support on credit and subside for seedling (

Table 15). As per the discussion of FGD participants, the main attention of the government is enhancing food security through expanding extension farming of annual crops. They have not given any concepts to the community regarding agroforestry. The availability and access to better quality seedling was low. As the table above indicates there are low governmental subsidies in providing species such as garden fruit and vegetables for the community. The respondents have argued that there is low accessibility to the germ which is productive for the community agricultural practices.

The kind of study and quality of germ-plasm available for farmers is coffee germ. However, the seeds of other fruits and vegetables were difficult to get for a long period. Members of FGD state that there was an absence of training for farmers and local change teams. This involves honestly training of farmers as trainers with the ultimate goal of farmers that trained would in turn provide training in agroforestry to fellow farmers in a given locality.